Rising Rents Pose Risks to the Fed’s Inflation Outlook

The biggest wildcard for U.S. inflation over the next year doesn’t come from used cars or airline fares. Instead, it is housing.

Officials at the Federal Reserve and the White House have highlighted what many forecasters expect will be the temporary nature of elevated price readings stemming from the reopening of the economy following pandemic-related restrictions.

But the degree to which 12-month inflation readings fall back to the central bank’s 2% goal could rest on the behavior of rents and home prices. In recent months, housing-cost trends point to more persistent, rather than transitory, upward price pressures in the coming years.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy costs, rose 3.5% in June from a year earlier, according to the Fed’s preferred gauge, the personal-consumption expenditures price index. That was the highest rate of growth in 30 years. Rising prices over the April-to-June quarter largely reflected disrupted supply chains, temporary shortages, and a rebound in travel—trends that came ahead of the latest virus surge caused by the Delta variant of the Covid-19 virus.

Economists at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimate that travel and other supply-constrained categories have added 1.2 percentage points to core inflation this year, and they forecast those contributions should wane to around 0.6 percentage point by the end of the year.

Contributions from rising rents and home prices could partially offset anticipated declines. In a June report, economists at Fannie Mae said they expected the rate of shelter inflation to pick up from around 2% in May to 4.5% over the coming years—and higher still, if house-price growth doesn’t cool off soon.

They forecast that by the end of 2022, housing could contribute 1 percentage point to core PCE inflation, the strongest contribution since 1990, and they forecast core inflation slowing to just 3% by then.

Housing inflation is important because it accounts for a hefty share of overall inflation—around 18% of core PCE inflation, and around one-third of a separate inflation gauge, the Labor Department’s consumer-price index.

Fed officials have held interest rates near zero since March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, and they are purchasing $120 billion per month in Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to provide additional stimulus. Just how fast and how far inflation falls back towards the Fed’s target one year from now could weigh heavily on how long to leave interest rates at zero.

Growth in rents slowed sharply during the pandemic as people stayed put or doubled up with family. Residential rents rose 1.9% over the 12 months through June, about half of the rate of growth seen in February 2020.

Before the pandemic hit, “we were treading water,” said Ric Campo, chief executive of Camden Property Trust, which owns and manages 60,000 apartment homes across 15 U.S. markets. Landlords lost any pricing power during the pandemic, as vacancy rates jumped.

But that began to change earlier this year as demand for new leases soared. “In March, it was like a light switch went off,” said Mr. Campo. “We have significant pricing power that we did not have a few months ago.”

Invitation Homes Inc., the largest single-family landlord in the U.S., raised rents by 8% in the second quarter, including 14% on leases signed by new tenants. Invitation reported occupancy of more than 98%, an extremely tight market.

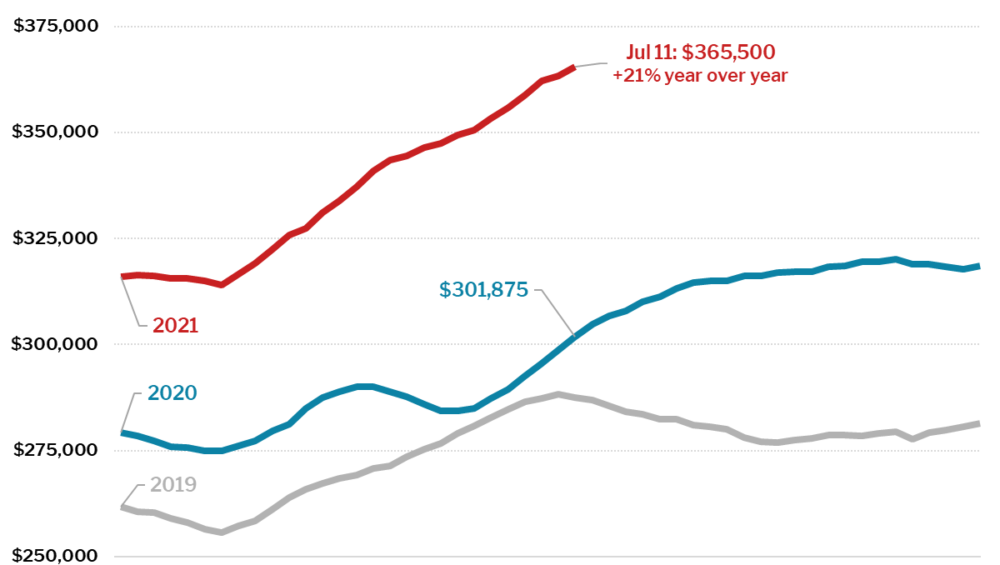

Home prices, on the other hand, never missed a beat. They surged during the pandemic, boosted by a combination of low mortgage rates, pandemic-driven changes in home preferences, favorable demographics, and low inventories of for-sale homes. Prices rose 16.6% in May from one year earlier, according to the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. national home price index, up from around 4% in the year before the pandemic.

Government agencies don’t take soaring home prices directly into account when calculating inflation because they consider home purchases to be a long-lasting investment rather than consumption goods. Instead, they calculate the imputed rent, called owners’ equivalent rent, of what homeowners would have to pay each month to rent their own house. Owners’ equivalent rents, which rose around 3.3% before the pandemic hit, cooled earlier this year, rising just 2% in the 12 months ended April.

Those measures tend to lag movements in home prices because leases are set for a year. The upshot is that leases signed one year ago, when landlords weren’t expecting to have much pricing power, are now coming up for renewal. As landlords pass along higher rents, annual inflation measures should soon start to pick those up.

“As the labor market improves and we have higher income and more household formation, that’s a lot of potential strength in rental inflation and in shelter inflation more broadly,” said James Sweeney, chief economist for Credit Suisse.

Even if recent eye-popping rates of rental increases can’t be sustained, housing analysts and executives see continued strong growth. Property tax increases from rising home values, for example, could be passed onto renters. Higher home prices could prevent more would-be buyers from becoming owners, which may keep pressure on rents.

Some of the housing market’s challenges reflect anemic new-home building that followed the 2008 bust. “We destroyed three-quarters of the supply chain, and a lot of resources left the business at the same time millennials were starting to emerge,” said Doug Duncan, chief economist at Fannie Mae. The result has been a shortage of houses and apartments in the places where many people want to live.

The pandemic, meanwhile, fueled new demand for housing. A recent study by Fed economists found that new for-sale listings would have had to expand by 20% to keep price growth at pre-pandemic levels.

A majority of economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal in July projected inflation would decline to at least 2.2% by the end of 2022. If the conventional wisdom among professional forecasters about inflation proves wrong, housing would be a big reason why.